This paper addresses how religion is playing an increasingly important role in empowering anti-nuclear protests at Gongliao in Taiwan. It begins by describing how the anti-nuclear movement in Taiwan was originally dependant on the opposition political party, and then examines how growing disaffection with party politics at Gongliao has resulted in a local temple dedicated to the goddess Mazu coming to the forefront of the struggle. This paper frames the dispute as a struggle between three different ways of generating power (and implicitly, of losing power): first, the generation of nuclear power by bureaucrats and scientists working through the industrial sector; second, the generation of political power by opposition politicians and elite campaigners; and third, the generation of religious power by people rooted in local communities, creating an alliance between religious power and secular protest.

Keywords: anti-nuclear; goddess Mazu; pilgrimage; politics; social movement; Taiwan

Introduction

Today, we recognise that the environment is a shared resource and a shared risk (Beck 1995). Environmental issues affect not just the living present but also the unpredictable future, and cannot be compartmentalised: beyond purely scientific calculations, these risks imply questions of morality, values and justice. In the wake of the nuclear disaster of March 2011 in Fukushima, Japan, Germany announced that i t would seek to end its reliance on nuclear power by 2022; following Germany’s lead, Taiwan’s presidential candidate for the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in January 2012, Dr Ing-Wen Tsai, campaigned for a nuclear-free Taiwan by 2025.

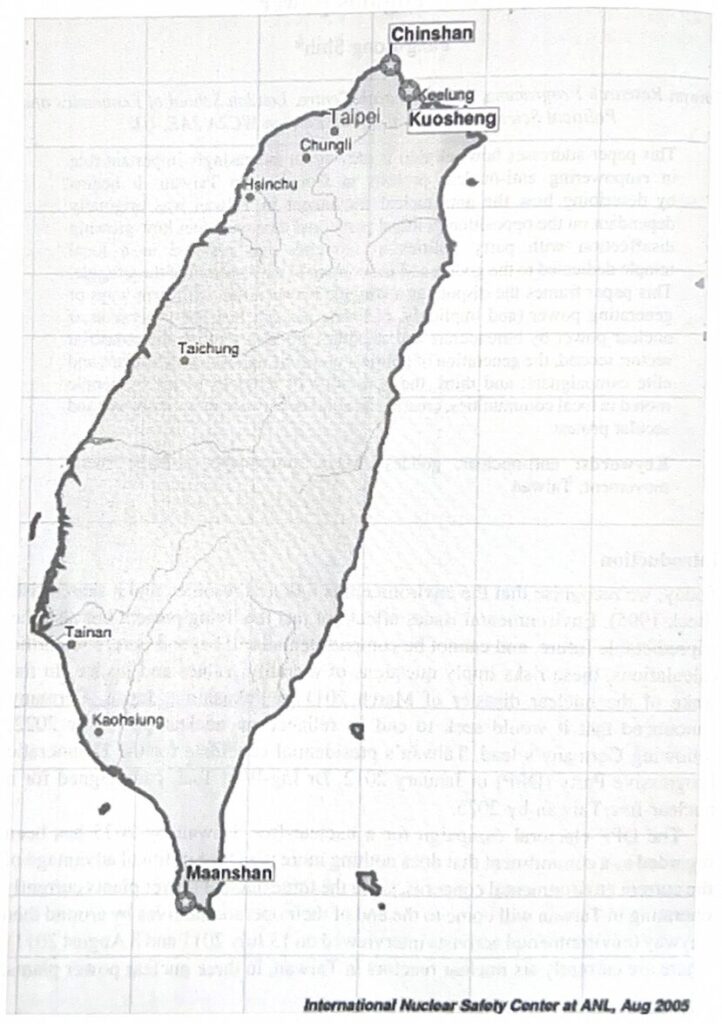

The DPP electoral campaign for a nuclear-free Taiwan by 2025 has been regarded as a commitment that does nothing more than take political advantage of the current environmental concerns, since the three nuclear power plants currently operating in Taiwan will come to the end of their operational lives by around then anyway (environmental activists interviewed on 13 July 2011 and 8 August 2011). There are currently six nuclear reactors in Taiwan, in three nuclear power plants: the Chinshan and Kuosheng plants are at the northern end of the island, while the third, the Maanshan plant, is at the southern end (see Figure 1).

The oldest reactors, at Chinshan, were originally due to expire in 2017-2018, while the others between 2021 and 2025. However, Chinshan has in fact been granted a 20-year extension to 2037-2038 (see Table 1).

| Units | Type installed | MWe gross | Start date | Licence expiry dates |

| Chinshan 1 | BWR | 636 | 1978 | 2037 |

| Chinshan 2 | BWR | 636 | 1979 | 2038 |

| Kuosheng 1 | BWR | 985 | 1981 | 2021 |

| Kuosheng 2 | BWR | 985 | 1983 | 2023 |

| Maanshan 1 | PWR | 951 | 1984 | 2024 |

| Maanshan 2 | PWR | 951 | 1985 | 2025 |

Source: World Nuclear Association, http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf115_taiwan.html (updated September 2011).

Given these scheduled closure dates for the older plants, the biggest debate in Taiwan today is over plans for a fourth nuclear power plant in Gongliao H E , an administrative district of New Taipei City (before 2011 known as Taipei County) on the north-east coast of Taiwan. This plan was first announced in 1980 and the plant is now due to become operational. Tsai’s view on this subject was reported in June 2011 in the Taipei Times:

When asked why she supported the continued construction of the Fourth Nuclear Power Plant, but not its eventual operation, Tsai said the compensation cost for breaching the construction contract still needed to be evaluated before a final decision could be made.

Given the significance of the Fourth Nuclear Power Plant, I therefore focused my fieldwork on grass-roots anti-nuclear activism around Gongliao. I was there for approximately 3 months, towards the end of September and into October 2010, and again during July and August 2011. The best-known campaign organisation in Gongliao is the ‘Yanliao Anti-Nuclear Self-Defence Association’ 鹽寮反核自救會, founded in 1988 and based in an area called Yanliao (an old name used by the local people), where the Fourth Nuclear Plant is located. Yanliao was originally a community of an aboriginal Austronesian people called the ‘Ketagalan’ (Danshui Community Studio 1997), and the Fourth Plant was built over pre-historic relics of their culture (Ketagalan Tribe Studio 1997).

The history of the anti-nuclear protest movement at Gongliao reveals a gradual two-stage process by which local opposition developed from a ‘party-dependent movement’ (Ho 2003, 683) into a party-independent movement. In the former stage, Taiwan’s anti-nuclear movement developed in relation to a particular political party, with which it remained intimately connected. In the latter stage, Taiwan’s anti-nuclear movement has created increasing distance from party politics and has become more autonomous; instead, an increasingly important role is now being played by religion in providing the necessary symbolic resources to empower more recent protests. In particular, the Mazu temple in Aodi zu (an old local name) in Gongliao district has played a role in the struggle against the Fourth Plant from the very beginning, but it has only been in recent years – in response to growing disaffection with the DPP – that it has come to the forefront of the struggle.

During my field research. I visited the Yanliao Association, Aodi’s Mazu temple and a re-constructed Ketagalan shrine, and I participated in some of the Association’s activities and temple rituals. I talked to a government official and a temple custodian, and I undertook in-depth interviews with leading figures in local environmental and cultural campaigns and in national environmental NGOs. I learnt from my informants about the movement’s 23-year history of struggle. In this paper, I frame the debate over Gongliao as a struggle over the generation of three different kinds of power, while also remaining attentive to related instances of loss: first, in the generation of nuclear power by bureaucrats and scientists; second, in the generation of political power by opposition politicians and elite campaigners; and third, in the generation of religious power by people rooted in local communities.

Generation of nuclear power

The end of the Second World War also ended 50 years of Japanese colonial rule in Taiwan. On the Chinese mainland, the Kuomingtang (Chinese Nationalist Party, KMT) was fighting a civil war against the Chinese Communist Party, and in 1949 the KMT retreated to Taiwan. Now confined to the island, the KMT sought continuity with the Republican legacy on mainland China and continuing legitimacy by attempting to turn Taiwan into a representation of China, naming it the ‘Republic of China’ (ROC). Martial law was declared and a policy of ‘sinicisation’ vigorously pursued. However, in the decades that followed, international recognition of the ROC declined: Taiwan lost its seat at the UN in 1971, the UK withdrew recognition in 1972 and the USA followed in 1979. With diplomatic failure and the loss of international legitimacy, the KMT government instead dedicated itself to rapid industrialisation and economic prosperity, and this, along with the oil crisis, prompted the KMT government from the early 1970s to begin importing nuclear technology. The nuclear industry has long been understood as bringing prestige; it is:

an industry that projects a national symbol and is closely linked to the issue of sovereignty. Strategic considerations have thus played a prominent role in the nuclear decisions of certain states, particularly during the Cold War, when some form of nuclear and/or energy security was considered a paramount concern by regimes in the East Asian region.

The electricity industry in Taiwan was a monopoly run by the state-owned and therefore KMT-controlled Taiwan Power Company. The task of developing nuclear energy was given to a small circle of KMT bureaucrats and scientists in the Atomic Energy Council, working with the Taiwan Power Company and its international business partners. In 1984, it was reported that:

Nuclear power accounted for more than 40 percent of all power generated in the Republic of China during the first half of 1984, according to findings by the Atomic Energy Council of the Executive Yuan. The ratio is the third highest in the world

Nuclear energy, it was claimed, would free Taiwan from dependence on foreign oil and be an economical way to meet the island’s growing energy needs. Under the KMT, Taiwan sustained high-speed, export-oriented industrial growth, creating a so-called economic miracle as one of the four ‘Little Dragons’ in East Asia (Vogel 1991). Electricity prices in Taiwan remained unchanged from 1983 to 2006 (Valentine 2010, 23), when a 5.8% increase was made (Wang 2008, 12).

Although nuclear energy generated a certain degree of wealth and prosperity over a short-term period, an anti-nuclear power movement began to gain attention from the mid-1980s, following various minor accidents at the six reactors and concerns over the safety and feasibility of the proposed Fourth Plant, including a controversial budget increase of 271% for the project in 1984. The biggest boost (if I can put it that way) to the anti-nuclear campaign was the Chernobyl accident in Ukraine in 1986. This demonstrated the actual danger of nuclear power and stimulated real fear, and led to the construction on the Fourth Plant being suspended (D. Chen 1994, 260). Whether to resume construction has been the biggest debate in Taiwan over the past two decades. As well as the fear of accidents, the site chosen for the Fourth Plant contains pre-historic relics of Ketagalan culture. Also, Yanliao has long been a fishing village, and the adjacent Fulong 福隆 has been promoted as a ‘golden beach’ resort since the Japanese colonial period.

Construction of the Gongliao plant was completed in early 2010, and technicians have since been conducting tests in preparation for getting it operational. However, there has been a series of accidents: for instance, it was reported on 9 June 2010 in Next Media that there had been a fire in the main control room for No. 1 Reactor; exactly a month later, the China Post reported that there had been a power-cut in the No. 1 Reactor system which had caused an outage of the entire plant for 28 hours (Guan and Mo 2010). Furthermore, in March 2011 came the Fukushima earthquake, tsunami and the consequent nuclear disaster. It was noted that Japan’s Prime Minister had to ask the USA for help, including technical advice, and the International Atomic Energy Authority was also monitoring the situation. The nuclear risk is a global risk – and no one country, let alone an individual person or village, can face it alone.

With the generation of nuclear power, local people fear they might lose their prosperity. This was expressed in a poster calling for a protest on 19 February 2011:

We should all be aware that we are always the last people to be informed about the real danger of the Fourth Nuclear Power Plant … The Fourth Nuclear Plant is close to completion. Job opportunities will soon become fewer and fewer, and in the near future more and more of our children and grandchildren will need to leave home to search for jobs elsewhere. If the Fourth Plant begins to operate, there will be fewer and fewer tourists because they will fear the risk of being contaminated by nuclear radiation.

It is still in doubt whether the Gongliao plant will become operational, although its construction has certainly already caused losses. These losses include pre-historic relics of Ketagalan culture (Ketagalan Tribe Studio 1997) and a reduction in the size of the golden beach at Fulong (Atomic Energy Council Committee 2006). Also, in 2005 it was established that nearby coral had declined by 50% since 1981 before the construction of the Fourth Plant (Environmental Protection Administration 2006). Unlike the generation of nuclear power that can be precisely calculated, the significance of these losses is immeasurable.

Generation of political power

As noted by Ho, the anti-nuclear movement in the West developed within the framework of liberal democracy, while the movement in Taiwan confronted ‘not a capitalism tamed by democracy, but rather a rampant capitalism without democratic accountability’ (2003, 686). Western environmentalists protested against their countries’ major political parties, which, according to Ho, were ‘too committed to the goal of growth with advanced technology to be responsive to the increasing nuclear skepticism’ (2003, 686). Environmentalism in Europe had thus weakened the left-right cleavage and gone beyond party politics. However, in the case of Taiwan, environmental movements addressed not only specific environmentalist issues, but were also more generally a part, though not necessarily consciously so, of the wider struggle for the democratisation of Taiwan. This meant, specifically, the liberalisation of Taiwan from martial law and from the one-party authoritarian rule of the KMT.

Although the KMT’s rule created economic prosperity, it also imposed a national Chinese culture on Taiwan and a rapid, ever-changing industrialisation. This was itself a kind of ‘colonialism’, which was no less ‘foreign’ than the Japanese colonial rule. It was a process of political domination by a Chinese state and a ruling class of waishengren (referring to those who came to Taiwan with the KMT from the mainland after 1947) at the cost of the suppression of Taiwanese people, history and culture, and at the price of the degradation of Taiwan’s soil, water, environment and ecological systems. Various social movements appeared from the late 1970s onwards, such as the dangwai (outside the KMT Party) movement, a s well a s farmers’ , workers’, women’s and environmental movements. These movements pursued their respective goals, but they all also challenged the KMT’s authoritarian rule.

The radicalisation of political opposition had a significant impact on environmental movements in general and on anti-nuclear movements in particular (Hsiao et al. 1999, 257). Indeed, the rise of the Gongliao anti-nuclear protest coincided with the emergence of the first opposition party—the DPP—in 1986, although at this time a few young KMT politicians were also in tune with anti-nuclear voices. The DPP was formally legalised in 1989, although martial law had been lifted in 1987. Significantly, the DPP included a statement opposing nuclear power in its party constitution (Chen 2005, 191). Within 4 months of the liberation of Taiwan from martial law, the first prominent environmentalist organisation was established, named ‘Taiwan’s Environmental Protection Union’ (TEPU). TEPU for the most part consisted of two small elite groups: university professors, mostly from National Taiwan University, and DPP politicians from a sub-group named ‘New Tide’ (Weller and Hsiao 1998, 89).

In May 1990, senior KMT official Po-Tsun Hao became Premier of the Executive Yuan. He had a military background and attributed a recent decline in economic growth to unruly protesters, whom he blamed for generating societal disorder and consequently scaring away investment opportunities. Hao reversed the suspension of the Fourth Nuclear Power Plant project and renewed its budget. He adopted a harsher attitude towards the burgeoning civil movements, authorising the police to take any action they judged necessary. One year later, on 13 October, an agreement with protesters was broken by police officers, leading to a violent clash with activists at Gongliao. This resulted in the accidental death of a policeman, who was killed by a car during the unrest, and several further officers and activists being injured. Seventeen activists were subsequently charged: these included the driver of the car, who received a life sentence, and the then-Executive-in-chief of the Yanliao Association, Ching-Nan Kao, who was given a 10-year prison sentence (Chen 2005, 74-77).

Continuing repression by the KMT in the post-martial law context forced anti-nuclear activists not just to oppose KMT authoritarianism, but also to become actively involved with party politics and explicitly aligned with the opposition DPP. Jun-Yi Lin, a professor of biology, is acknowledged by some to be the ‘father’ of Taiwan’s anti-nuclear movement (Ho 2003, 690). Reflecting on Taiwan’s history of authoritarian repression, he commented on the relationship between environmentalism and politics in Taiwan in the Independent Eveninisation Post on 3 August 1992:

Owing to the fear of politics in the past, environmentalists avoided the politicisation of [the] ecological movement, i.e., the democratic movement. This is one of the reasons why the ecological and environmental movement in Taiwan cannot expand In the future 2 1 century, [the] political movement must go ecological and humanized, while the ecological movement must be politicized.

The DPP, ever since its founding, had taken a clear stand against the KMT’s pro-nuclear power policy. Moreover, some young DPP activists, through their involvement with the founding of TEPU and participating in TEPU’s activities, developed a platform for allying with local people and civic organisations to campaign on significant social issues in defiance of the KMT’s authority. In return, the DPP gained support and votes from anti-nuclear power activists and from those adversely affected by nuclear power. By joining an organised political party, environmental activists felt empowered by their political alliance in terms of political influence, financial resources and media visibility. Some elite activists campaigned for the DPP or even eventually stood for positions as DP government officials: these included Jun-Yi Lin and Kuo-Long Chang. Chang was a professor of physics, one of the founders of TEPU, and also regarded by some as the ‘father’ of Taiwan’s anti-nuclear movement (Chen 2005, 64). This early-stage strategy forged close connections between anti-nuclear protests and political opposition to the KMT, and paved the way for a one-sided and one-party-dependent paradigm.

In the 1990s the anti-nuclear movement in Taiwan was tied closely to the fate of one particular party, the DPP, and this party’s electoral performance and success. As the DPP increased its political power, winning extra seats in the Legislative Yuan and control of the Taipei County Government, it was a helpful ally for the movement. The DPP’s Ching You, who was Magistrate of Taipei County from 1990 (the first multiparty election) to 1997, in particular received 71.2% of the vote at Gongliao in the 1993 election (Chen 2005, 101). This shows that the DPP enjoyed the advantage of monopolising the growing market of anti-nuclear votes. One DPP leader commented that *we had been able to mobilize people on political issues. We could now do the same thing on environmental issues’ (Ho 2003, 695). Indeed, at this time, every single protest event generated further anti-KMT sentiment and created further gains for the DPP. As a result, anti-nuclear voices within the KMT fell silent one after another. One example was Shao-Kang Chao, who was Director of the Environmental Protection Administration between 1990 and 1992 for the KMT; Chao was originally against the Fourth Plant, but he dropped his objection.

It was clear that the battle between pro- and anti-nuclear campaigning in Taiwan had become consolidated along the cleavage of party politics between the pro-China KMT and the pro-Taiwan DPP. However, just as Taiwan’s anti-nuclear movement had originally gained recognition because of its close connection with the increasing power of the major opposition party, it went into decline for the same reason. This was certainly the logical outcome of being a party-dependent movement: conventional theories about social movements present them as civil society agents ‘used by people who lack regular access to institutions, who act in the name of new or unaccepted claims and who behave in ways that fundamentally challenge others or authorities’ (Tarrow 1998, 3). In Taiwan, the situation was complex: civil society, defined a s ‘ a realm outside political parties where individuals and groups aimed to democratize the state, to re-distribute power, rather than to capture power in a traditional sense’ (Kaldor 2003, 9), did not exist when concerns about nuclear power were first raised on the island

By 2000, despite struggling for 13 years, the anti-nuclear party-dependent movement still had not managed to achieve its goal of abolishing the plan for the Gongliao plant. This failure, though, in no way hindered the DPP from achieving power: in March 2000, Shui-Bian Chen became the first non-KMT-elected President, in part at least due to his pro-environment platform. According to my informants, it was at first widely believed among people in Gongliao that the abolition of plans for the Fourth Plant would become a reality sooner or later. However, in May 2000, it was reported that ‘scrapping the project would cost NT dollars 100bn, including compensation for breaking contracts already awarded to local and foreign builders’ (Central News Agency 2000), and that this would require increases to tax and electricity costs. Nevertheless, on 27 October 2000, it was unexpectedly announced by the DPP Premier, Chun-Hsiung Chang, that the project had been abolished, even though the matter had not been put to vote in the Legislative Assembly as required by the constitution.

The local people at Gongliao were shocked and uncertain at this turn of events. The then-chairman of the Yanliao Association, Wen-Tung Wu, recalled the moment when he heard this news, saying that:

None of our members had been informed of this decision in advance, and I felt it was a bad sign. This meant that the room for open discussion among different political parties regarding clean energy had been closed. The DPP abolition would only bring about an opposite result – an absolute objection from the KMT and its allies.

For the first time since the Presidential election defeat, divisions within the KMT and its allies were overcome in objection on constitutional grounds to the DPP’s course of action. On 15 January 2001, the cancellation was blocked by the Council of Grand Justices (Alagappa 2001, 16-17), and on 31 January 2001, the Gongliao plant project was finally put to vote in the Legislative Assembly. There were 134 votes for continued construction, versus 70 votes for abolition. One hundred and ten days after the abolition had first been declared, the same Premier Chang announced the exact opposite course of action: construction o f the Fourth Plant would be restarted. Chang expressed several times that it was a ‘painful decision’, but he added that ‘if we allow this standoff to continue, it will cause economic and social chaos’ (Foreman 2001).

The shock and confusion at this further turn of events was certainly great among Gongliao people. After 13 years of struggle, it became apparent that the anti-nuclear power principle had been sacrificed in the competition for political power and in the name of reconciling party conflicts and interests. As Chen (2005, 180–195) observes, it appears that the ex-ruling KMT could not accept having lost the Presidential office for the first time, and that it was attempting to bring about the collapse of the newly elected DPP government by mobilising its majority of seats in the Legislative Assembly to reject the DPP’s plans for the Fourth Plant. However, it was also the case that the DPP’s strategy and method for opposing the Fourth Plant had been poorly conceived and ill-planned. To complicate the matter further, the issue of nuclear power goes beyond domestic politics: considerable economic and political interests of superpowers and multinational companies were involved, affecting the delicate balance of international relations.

However, blame was passed from the DPP government to the local protesters, whose social status was marginal and who were without political resources. Mr Wu went on to recall this period:

It was unbelievable and unacceptable that not only the KMT but also the DP blamed us [the Yanliao Association] for the [potential] waste of million dollars of taxpayers’ money and for being responsible for the economic downturn in Taiwan referring to the late 1990s economic crisis in Asia] because we opposed the construction of the Fourth Nuclear Plant.

Through interviews with many other protesters at Gongliao, I could tell that to various degrees they all felt that they had been deceived or even betrayed by the DPP at that time, and discussions of the anti-nuclear issue quickly turned to the DPP’s perceived manipulation of the situation. Consequently, the anti-nuclear campaign had become a sensitive subject and local people became too demoralised to continue to assert their anti-nuclear position publicly. I was told that over the previous decade, hard-line and elderly protesters had passed away one after another, while many others were suffering from depression.

The DPP and its allies had generated political power to a great extent from opposition to nuclear power. However, this political power did not benefit the anti-nuclear campaign while the DPP also lost power to the KMT in the 2008 presidential election. Dr sai’s presidential election campaign for the DPP in 2012 included a call for a nuclear-free Taiwan by 2025, but she lost to the KMT by a small margin.

Generation of religious power

In September 2010, when I began my first fieldwork period, the Yanliao Association’s campaign seemed to have just come back to life after almost a decad of quiet. The construction of the Gongliao plant was somehow finished in early 2010, and it will be operational once the safety tests have been completed. It was difficult for Gongliao people to revive their campaign after the harmful political developments of 2000, and they were now without assistance from any of Taiwan’s political parties. I discovered that an alternative resource was being accessed by the local people to generate the power they needed, namely their local Aodi temple’s goddess Mazu. Aodi’s Mazu temple is situated adjacent to the Fourth Plant, and the temple’s main deity – goddess Mazu – has long been addressed as ‘the anti-nuclear power goddess Mazu’ 反核媽祖. In particular, I was told by one informant after another about a prediction made by the goddess on the sixth day of the third lunar month in 1988, to the effect that although the Fourth Plant at Gongliao would eventually be built, it would not be able to generate electricity.

The Aodi’s Mazu temple was founded between 1821 and 1850 by women both of aboriginal Ketagalan and of Han Chinese ancestry. It is claimed that Han people first settled in this area around 1773, and that Han and Ketagalan peoples lived peacefully in this fertile lowland area. One day, Chinese Han women and Ketagalan women were working together to collect shellfish and other seafood along the coast in Mountain Flame valley when they saw a wooden statue standing between two rocks. A Chinese woman recognised it as the goddess Mazu, while a Ketagalan woman brought it back and accommodated it in a local shrine of the Earth God. The news that Mazu had appeared in Aodi eventually spread all over Gongliao. Many people came to worship the goddess, asking for her help and guidance, and Mazu seemed to give efficacious responses to all requests. In return, worshippers donated money, and a proper temple was built to house the goddess herself in 1854. It was given an official name ‘Ren-He’ 仁和, meaning ‘merciful and peaceful’ (Ren-He Temple Management Committee 2004).

The Aodi’s Mazu temple has been categorised typologically as a territorial cult. Sangren describes the characteristics that are found combined in such territorial cults:

The first is … cultural: a territorial cult coalesces around worship of a deity who is conceived as having jurisdiction over a certain spatial territory. The second is sociological: territorial cults are concretely constituted in communal rituals. It is at these rituals that community members congregate and act as a corporate body.

Mazu, the Goddess of the Sea, has long been the patron deity of fishermen and majority of the adult population in Gongliao has long been involved in the fishing industry. Indeed, the Gongliao neighbourhood was patterned mainly by fishing networks and these historically determined how both Ketagalan and Han people interacted with each other and also related to place, land and sea. Gongliao social space and networks further affected the cultural construction of the local Mazu cult, and the formation of her territory and community. In other words, Gongliao social interaction and space thus became ritually defined as a territorially discrete unit under the authority of the patron goddess Mazu.

This further reflects what Weller has demonstrated in Alternate Civilities, that: ‘in some cases, temples were the only important organizations uniting villagers as communities. The close ties between temples and communities made religion an important nexus of power and action’ (1999, 31). Nevertheless, it should be noted that Mazu’s power and authority are not hierarchically authoritarian, but are rather attributed mainly to notions of what Sangren articulates as ‘ling (efficacy, [spirit power 靈]) and virtue’ (1987, 55).

In Chinese popular belief, deities are typically depicted in anthropomorphic form and are usually identified as the spirits of former human beings who led unusually meritorious lives in society (Shih 2010, 237). The goddess Mazu was identified as the spirit representation of a virtuous maiden named Mo-Niang Lin (960-987 C.E.). She was the sixth daughter of a virtuous official of low rank named Wei-Ke Lin, who lived on Mei-Zhou Island in Fu-Jian province. Mo-Niang did not marry, and instead devoted herself to religious practices. She suffered an early death at the age of 27, but towards the end of her short life local people became convinced that she had special power and that during trances her spirit would leave her body to guide fishermen safely home through storms. The first indication of this came from a miracle in which she was credited with saving her father and brother. After Mo-Niang died, fishermen continued to report similar incidents, and the identification of Mo-Niang Lin as Mazu, the Goddess of the Sea, was gradually constructed (Watson 1985, 295-96).

Goddess Mazu i s worshipped not only in times of distress such a s when fishermen are lost at sea, but also more generally to safeguard the fishermen in their activities. Similarly, whenever Gongliao fishermen have been at a loss for what to do during the anti-nuclear campaign, they have consulted goddess Mazu for help and guidance. Ling is conceived as the power possessed by spirits and deities, and this is the underlying premise of ritual activity in Chinese religious culture. The 1988 prediction story that demonstrated the spirit power of the goddess Mazu can b e summarised a s follows:

A few days after the Yanliao Association had been established in 1988, one of Gongliao’s most senior men cast poe ト筊, or divination ‘moon blocks’, to communicate with the goddess Mazu on behalf of the township. The first question he asked was whether ‘construction of the Fourth Plant will not be completed’. This question did not receive siu-poe 聖筊, even after several castings. He then asked if the Fourth Plant would be built, and this time he obtained siu-poe. After this, he then asked the question in a different way, whether ‘the plant will not be able to generate electricity’. This time, he obtained several siu-poe.

This is a common way to communicate with a divine agency in Chinese religious culture. Two blocks, normally made of wood, are cut into the shape of a crescent moon, rounded on one surface and flat on the other. In divination, the diviner usually holds the blocks out on his or her two palms, and raises them to the level of his or her forehead. After articulating his or her question, the diviner then quickly drops the blocks onto the floor. There are three possible combinations that result, each of which has a specific meaning: one flat side down and one rounded side up which is taken to indicate agreement, and so this position is called siu-poe, ‘affirmative poe’; if both blocks land rounded side down, the way they rock on the floor before coming to rest is interpreted to mean that the deity finds the statement to be odd and is amused at it and so this position is called chhio-poe 笑筊, ‘laughing poe’; if both blocks land flat side down, their lack of movement is understood to mean that the deity is somewhat angered by the request, and this position is called im poe 陰筊, ‘disaffirmative poe’. It is important to note that although the last two positions suggest negative replies to the question put to the deity:

interpretations of negative replies are seldom taken very seriously … and what is important is to determine what form of a statement the [goddess] will confirm as a correct statement of … [her] point of view, rather than to develop an emphatic yes or no to a given question.

In the 1988 divination, the goddess Mazu seemed t o be showing that the Fourth Plant at Gongliao would eventually be built but that it would never be operated to generate electricity. However, this 1988 prediction was not taken seriously until 2010, when people i n Gongliao came t o realise that the Fourth Plant had by then been completely constructed (as predicted by Mazu in 1988). This prompted a revival of campaigning against the plant being operated but this time the protesters could no longer rely on any political party through which to generate oppositional power. The notion of ling, as understood by Sangren, ‘is not only a key operator underlying the logic of relations among religious symbols, but also both a product and a generator of the social relations reproduced in ritual activity’ (1987, 131).

Indeed, Mazu’s efficacy, in terms of her spirit power, is generated both in sacred rituals and in secular activities that take place around her. In having become distanced from party politics, people in Gongliao have retreated into their local community and are instead turning to their patron goddess, recalling her power and words. Mazu’s prediction of the fate of the Fourth Plant was thus recalled and reinvented as a resource to sustain their protest. It is the hope of the

Gongliao campaign that, in accordance with Mazu’s prediction, although the Fourth Plant will be completed, it will never be able to generate power.

In July 2011, when I conducted my second period of fieldwork, the Yanliao Association’s campaign was thriving again. The revival of the campaign was, no doubt, due to a series of accidents that had occurred during safety tests in the Gongliao plant, and further anxiety and energy was generated from early March after the nuclear disaster at Fukushima in Japan. The Mazu temple and its rituals have become the centre of the revived Gongliao anti-nuclear campaign.

In fact, the Mazu temple has, since its establishment, been the centre of the Gongliao domain. As Sangren notes, the primordial “determinants” of ritually institutionalized community may be forgotten or disappear, yet the community and its ritual persist’ (1987, 62). Once the Mazu cult had been institutionalised, by the time of the construction of the Ren-He temple in 1854, the Gongliao Mazu community and ritual took on an independent existence. This can be seen from a series of temple rebuildings undertaken by the community of the Mazu cult territory: following the original 1854 construction, the temple was extended in 1880, removed and rebuilt in 1918, refurbished in 1946 and expanded in 1957 (Ren-He Temple Management Committee 2004).

The climax of the communal rituals is the annual Mazu pilgrimage, which takes place on her birthday, the 23rd day of the third month. As highlighted by Sangren, ‘although territorial-cult . . . temples stand as permanent symbols of ritual community, a temple does not itself constitute a territorial cult; rituals do’ (1987, 55). At the Mazu pilgrimage, the Gongliao community members congregate and act as a corporate body: pilgrims arrive in groups, organised by various religious associations in the territory, and visit the Ren-He home temple to regenerate the spirit power of their branch statues by passing them through the smoke of the home temple’s incense burner. It is widely observed that pilgrimages promote social and cultural integration among different groups that may otherwise lack a focus for common identity. In Turner’s words, pilgrimages express the ‘inclusive, disinterested, and altruistic domain’ and embody the spirit of ‘communitas’ that ‘presses always to universality and ever greater unity’ (1974, 186, 179). Indeed, pilgrimages have a socialising impact on individual pilgrims. Through pilgrimages, individuals experience enhanced feelings of sisterhood and brotherhood, and can acquire social identities that transcend political, ethnic and status differentiation.

It is interesting to note that since the 1990s along with the development of Taiwan’s nationalism, Mazu worship and pilgrimage has had increasing appeal beyond any particular local territory and has been arising into an island-wide cult in Taiwan. As such, connections between Taiwanese identity and belief in the island’s patron goddess Mazu have been solidified. The goddess Mazu has therefore played a role in the defining of a Taiwanese identity (Rubinstein 2003; Sangren 2003). In this case study, the Aodi’s Mazu cult has been incorporated into and further transformed as part of the Gongliao anti-nuclear protest, as well as a part of the Taiwan-wide anti-nuclear campaign.

Indeed, the first anti-nuclear protest in Taiwan’s history was organised by TEPU and held in the Aodi’s Mazu temple yard on the first anniversary of the Chernobyl accident. Six days after the Yanliao Association’s launch in 1988, members gathered in front of the main statute of the goddess Mazu, burning a lorry-load of free calendars that had been given out to them by Taiwan Power Company, as a ritual to vow that they would no longer be bribed by any agency with an interest in nuclear power. Since its establishment, the Yanliao Association has taken part in the Mazu pilgrimage every year. Then-chairman Mr Wu explained to me that: ‘In the very beginning—not long after the lifting of martial law—people here still feared to march in the street. So, we carried our Association flag [which expressed an anti-nuclear message] on the Mazu pilgrimage instead’ (interviewed on 23 July 2011). After a pause, Mr Wu added:

Campaigning needs money. On the pilgrimage, we also carry a box to raise funds. Whoever donates money, his/her name and the amount of the donation are recorded on a sheet of red paper. These sheets of red paper are then all strung along a rope. After the pilgrimage, this rope is displayed in the Mazu temple. It is by Mazu’s blessing that we usually raise enough funds for the year.

Furthermore, in 1993 a Mazu statue was carried by people from Gongliao for the first time to the Legislative Assembly in Taipei and placed on a table behind the chairperson, where she could monitor the legislators’ review of the increasing budget for the Fourth Plant. In June 2000, a presidential election victory celebration was held in the Mazu temple yard, hosted by the DPP Minister of Economic Affairs on behalf of President Chen in the form of an outdoor banquet. On 29 August 2010, one hundred Gongliao people, together with the Green Citizens’ Action Alliance 綠色公民行動聯盟, assembled in the temple yard to protest for the first time in a decade by forming a human chain (i.e. hand-in-hand) around the plant (A-Jing 2010).

All of these events took place either in front of a Mazu statute or in her temple yard, symbolising her patronage of these events. Obviously, there are both pro-KMT groups and pro-DPP groups in Gongliao, but the people of Gongliao have now formed one voice to oppose the operation of the Fourth Plant. It was the goddess Mazu who unified voices that might otherwise or in other circumstances have fractured along party lines. The Yanliao Association has since its second revival become an independent, self-organised association, asserting a certain degree of autonomy.

Following the Fukushima disaster, there have been further developments. New voices from Japanese protesters were heard in the Aodi’s Mazu temple yard, warning that ‘although we cannot resist the occurrence of an earthquake, we can resist the operation of a nuclear power plant!’ (cited by an informant, interviewed on 8 August 2011). People in Taiwan have also come to realise that although paying compensation for a breached contract would be hugely expensive, the financial cost of a disaster such as that at Fukushima would be considerably greater, while the cost to the environment would be almost impossible to quantify. On 30 April 2011, the Yanliao Association co-organised an island-wide demonstration, with the message do not let Taiwan become the second Fukushima!’, and further urging Taiwanese people, ‘no matter whether you are Blue |KMT] or Green [DPP], stand up to protest for a nuclear free and safe Taiwan’ (vanliao Association 2011). In June 2011, a Mazu statue was once again carried by people from Gongliao, and placed next to a banner in front of the Legislative Yuan with the slogan: ‘Anti-nuclear power is in Taiwan people’s common interest’. As such, we see that the goddess Mazu has facilitated an island-wide anti-nuclear protest, generating the hope that she can unify support for the campaign from across the political spectrum all over Taiwan.

Construction at the Gongliao plant has suffered continued delays: welds failed inspections and had to be redone, and subcontractors renegotiated their contracts due to ‘the rising cost of steel, concrete and other commodities’ (Katz 2007). A confidential diplomatic cable from the American Institute Taiwan dating from 2005 and released by WikiLeaks also noted rising costs, along with problems such as the lack of ‘a single project manager’ and of a ‘single integrated time schedule’ (2010). As the project went over-budget, a group called the No Nuke Union Taiwan filed a lawsuit in 2006 claiming that a new budget increase had been illegal (Agence France-Presse 2006). The project has nevertheless now been completed, and technicians have begun to test the plant in preparation for getting it operational.

According to my informants, excessive delays in the plant’s construction have meant that some parts are out-of-date or even discontinued, and that some of the senior nuclear scientists involved in the project have retired or even died. Tests at the plant have revealed additional problems. I was told that the story of Mazu’s 1988 prediction is spreading over the region and that some of the plant workers have begun to panic, checking with the temple if Mazu really said that ‘The Fourth Plant at Gongliao would eventually be built but that the plant would not be operated to generate electricity’.

At the time of the completion of this paper, the Fourth Nuclear Power Plant in Gongliao is still not able to operate to generate power. This means that the 1988 Mazu prediction is still valid. It remains to be seen what will happen if the plant begins operation. Would this be interpreted as meaning that the goddess Mazu has lost her ling, or spirit power? Would her followers abandon her? Or would a new interpretation allow her to continue to generate religious power?

Conclusion

This paper has analysed the debate over Gongliao as a struggle between three different ways of generating power, and has further evaluated the gains and losses entailed in each case. First, we have seen that the generation of nuclear power has resulted in electricity prices in Taiwan remaining unchanged for 23 years, from 1983 to 2006. It was claimed by the ruling bureaucrats and industrial sector that the generation of nuclear power contributed to Taiwan’s economic growth during the oil crisis, leading to the achievement of a so-called economic miracle in which Taiwan become one of East Asia’s ‘Dragon’ economies between the 1970s and the 1980s.

However, while the gains from the generation of nuclear power are measurable, the risks are unpredictable and the significance of losses to culture, community and environment are unquantifiable and irreversible. Beck has critiqued what he calls ‘the failure of techno-scientific rationality in the face of growing risks and threats from civilization’. This failure, he argues, ‘is systematically grounded in the institutional and methodological approach of the sciences to risks … the sciences are entirely incapable of reacting adequately to civilizational risks, since they are prominently involved in the origin and growth of those very risks’ (Beck 1992, 59).

Second, the DPP government’s performance on anti-nuclear issues during its 8 years in power shows that the environment came second to the generation of political power. The DPP and its allies generated political power at least in part from opposition to nuclear power. The DPP can claim consistently to have been opposed to the Gongliao plant, but the fact remains that they chose a course of action that was unconstitutional and thereby bound to fail. It is beyond the scope of this paper to speculate as to why the DPP chose to pursue such a frankly bizarre course of action; although Jacobs (2012, 175-80) has given some attention to the course of events, this is still a subject that deserves further investigation.

In Taiwan, the process of political transition to democracy was driven by an opposition political party, and this enforced the political polarisation of society. This explains not only the strength of social movements before transition, when the opposition party needed their support, but also their decline post-transition, when the power of the anti-nuclear movement was transferred to the political opposition. In other words, the DPP to some extent facilitated the anti-nuclear protests, and the protests were therefore ‘tamed’ in terms of being integrated into the opposition political process and the institutionalisation of the DPP.

Third, democratisation actually weakened social movements as new political channels opened up, leading to a return to religion. In the Gongliao case, the anti-nuclear movement has now been revived and generates new power from the goddess Mazu, who plays an important role in Taiwan’s social structure, standing for cultural and national identities at the level of the shared historical experience of Taiwanese in general. Mazu pilgrimages bring together individuals and groups for a sacred purpose, and also serve as platforms for secular organisations to address social campaigns. Thus, pilgrimage is a form of meaningful social action that generates a socially constructed notion of power. As such, the Mazu cult is not just a product of social history, but also an arena for further cultural construction of that social history. We witness that religion has replaced a more standard political connection as a way for this social movement to achieve its goals. There is also a gendered aspect to this: the religious power of maternity generated by the goddess Mazu has replaced the political power of father figures in the anti-nuclear campaign.

In this clash between the science of nuclear power and the religion of spirit power, we can see that spirit power has served as a source of practical rationality and ethical insight, sustaining a meaningful debate despite political disappointment. There is a contrast: on the one hand, the informational dimension of nuclear science has generated not rational debate and consensus over agreed evidence, but rather division and disagreement over the question of risk. However, on the other hand, the transformational dimension of religious power, through its capacity to generate sustainable insights and relationships, has been able to connect individuals, groups and communities to their pasts and futures.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express her gratitude to the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy for an award, without which much of the field research would not have been possible.

References

Agence France-Presse. 2006. Reactor installed at Gongliao site. Taipei Times, 6 October 2006. http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2006/10/06/2003330586

A-Jing. 2010. 諾努客音樂會與反核圍廠人錬 [Report on no nukes gig and a human chain protest surrounding the Fourth Nuclear Power Plant]. http://cmching19.blogspot.com/2010/09/20100829_06.html

Alagappa, Muthiah. 2001. Introduction: Presidential election, democratization, and cross-strait relations. In Taiwan’s presidential politics: Democratization and cross-strait relations in the twenty-first century, 3–47. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Atomic Energy Council Committee. 2006. 核能四廠廠址福隆沙灘變遷調查 [Investigation into change at the beach in Yanliao and Fulong]. Taipei: Executive Yuan.

Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk society: Towards a new modernity. Thousand Oaks, CA/London: Sage.

— — . 1995. Ecological politics in an age of risk. Cambridge: Polity. Central News Agency. 2000. Scrapping Taiwan’s Fourth Nuclear Plant to impact growth. BBC Monitoring international reports, 8 May.

Chen, Chien-Chih. 2005. 政治轉型中的社會運動策略與自主性: 以貢寮反核四運動為例 [The autonomy of the social movement in the process of political transition: A case study of the anti-Fourth Nuclear Power Plant project movement in Gongliao]. Masters diss., Department of Political Science, Soochow University.

Chen, David W. 1994. The emergence of environmental consciousness in Taiwan. In The other Taiwan: 1945 to the present, ed. Murray A. Rubinstein, 257–86. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Danzai Community Studio. 1997. 凱達格蘭紀念中心設置計畫書 [The program of activity and culture center of Ketagalan]. Banqiao: Taipei County Cultural Centre.

Environmental Protection Administration. 2006. 潛水觀察核四海底 珊瑚礁生態報告 [Underwater investigation into the ecological conditions of coral next to the Fourth Nuclear Plant]. Taipei: Executive Yuan.

Foreman, William. 2001. Taiwan orders Fourth Nuclear Plant work to start. Independent, 14 February. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/taiwan-orders-fourth-nuclear-plant-work-to-start-691785.html

Guan, Yu. and Yun Mo. 2010. 反核的昨日今日明日 [Anti-nuclear protests: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow]. http://www.taiwangoodlife.org/story/20100909/24559

Ho, Ming-Sho. 2003. The politics of anti-nuclear protest in Taiwan: A case of party-dependent movement (1980–2000). Modern Asian Studies 37, no. 3: 683–708.

Hsiao, Hsin-Huang, Hwa-Jen Liu, Su-Hoon Lee, On-Kwok Lai, and Yok-Shiu Lee. 1999. The making of anti-nuclear movements in East Asia: State-movements relationships and policy outcomes. In Asia’s environmental movements: Comparative perspectives, ed. Yok-Shiu Lee and Alvin So, 252–68. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

Jacobs, J. Bruce. 2012. Democratizing Taiwan. Leiden: Brill.

Jordan, David. 1972. Gods, ghosts and ancestors: Folk religion in a Taiwanese village. Berkeley, CA: University of California.

Kaldor, Mary. 2003. Civil society and accountability. Journal of Human Development 4: 5–26.

Katz, Alan. 2007. Nuclear bid to rival coal chilled by flaws, delay in Finland. Bloomberg News, 4 September. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=aFhySy5JYQz.

Ketagalan Tribe Studio. 1997. 台北縣貢寮鄉核四廠區內凱達格蘭族文化遺址處理紀要 [Report on the conservation of Ketagalan cultural relics discovered under the Fourth Nuclear Power Plant in Gongliao township in Taipei County]. Keelung: Alliance of Taiwan Indigenous Culture.

Lee, I-Chia. 2011. Tsai asserts her nuclear stance. Taipei Times, 27 June. http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2011/06/27/2003506789

Ren-He Temple Management Committee. 2004. Introduction to Ren-he Gong. Taipei: Ren-He Temple Management Committee.

Rubinstein, Murray. 2003. ‘Medium/message’ in Taiwan’s Mazu-cult centers: Using ‘time, space, and word’ to foster island-wide spiritual consciousness and local, regional, and national forms of institutional identity. In Religion and the formation of Taiwanese identities, ed. Katz Paul and Murray Rubinstein, 181–218. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sangren, Steven. 1987. History and magical power in a Chinese community. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

— — . 2003. Anthropology and identity politics in Taiwan: The relevance of local religion. In Religion and the formation of Taiwanese identities, ed. Katz Paul and Murray Rubinstein, 253–87. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Shih, Fang-Long. 2010. Women, religions, and feminisms. In The new Blackwell companion to the sociology of religion, ed. Bryan S. Turner, 221–43. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Taiwan Info. 1984. N-power capacity ratio ranked 3rd. Taiwan Info, 23 December. http://taiwaninfo.nat.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=124869&CtNode=103&htx_TRCategory=&mp=4

Tarrow, Sydney. 1998. Power in movements: Social movements and contentious politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Turner, Victor. 1974. Dramas, fields, and metaphors: Symbolic action in human society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Valentine, Scott Victor. 2010. Disputed wind directions: Reinvigorating wind power development in Taiwan. Energy for Sustainable Development 14: 22–34.

Vogel, Ezra F. 1991. The four little dragons: The spread of industrialization in East Asia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wang, Lisa. 2008. New energy policy needed: CPC. Taipei Times, March 24. http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/biz/archives/2008/03/24/2003406921.

Watson, James. 1985. Standardizing the gods: The promotion of T’ien Hou (‘Empress of Heaven’) along the south China coast, 960–1960. In Popular culture in late imperial China, ed. David Johnson, Andrew Nathen, and Evelyn Rawski, 292–324. Berkeley, CA: University of California.

Weller, Robert, and Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao. 1998. Culture, gender and community in Taiwan’s environmental movement. In Environmental movements in Asia, ed. Arne Kalland and Gerard Persoon, 83–109. London: Curzon.

Weller, Robert. 1999. Alternate civilities: Democracy and culture in China and Taiwan. Boulder, CO: Westview.

WikiLeaks. 2010. Taiwan’s Fourth Nuclear Power Plant: Hurdles. Cable 05TAIPEI1640, created 6 April 2005. American Institute Taiwan, Taipei. http://wikileaks.org/cable/2005/04/05TAIPEI1640.html

Yanliao Association. 2011. 不要讓貢寮變成下一個福島! 430 反核四活動 [Do not let Gongliao become the next Fukushima! 30 April anti-Fourth Nuclear Plant campaign]. http://www.wretch.cc/blog/giyu1323